Tuesday, 13 February 2024 — National Security Archive

Advised that Telcons Were “Personal Papers,” Kissinger Expected to Keep Them When He Left Office

Likelihood of Bad Publicity and Lawsuits Changed His Mind

State Department Lawyer: “These records are not subject to the FOIA”

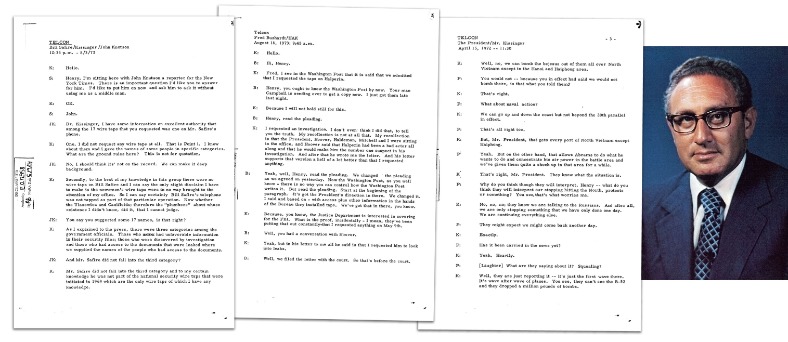

Washington, D.C., February 13, 2024 – State Department lawyers advised Henry Kissinger that transcriptions of his telephone conversations made when he served as national security adviser and Secretary of State were his personal papers and not “subject to disclosure under the FOIA,” according to recently declassified records from the U.S. National Archives and Records Administration (NARA). When Freedom of Information Act requests, the possibility of lawsuits, and bad publicity complicated Kissinger’s ability to maintain control over these records, the lawyers suggested that he could stash the so-called “telcons” away in the Library of Congress. Kissinger’s subsequent decision to do precisely that put them out of reach of the FOIA for decades, until the National Security Archive forced NARA and the State Department to begin to recover more than 15,000 pages of telcons in 2001.

The newly declassified documents, which come mainly from the files of the State Department Legal Adviser, shed new light on decisions taken during the early stages of Kissinger’s effort to shield the telcons from public scrutiny.

When Kissinger joined the Nixon administration as national security adviser in January 1969, he routinely had his telephone conversations transcribed for his office files. That continued when he became Secretary of State in September 1973. For the most part, only a few White House and State Department insiders knew of this practice or that Kissinger had taken the collection of White House transcripts with him to State, under the watchful eye of Deputy Under Secretary Lawrence Eagleburger.

New York Times columnist William Safire, a former Nixon White House staffer, broke the news about the telcons in 1976 and also filed one of the first FOIA requests on the secret bugging operation, which was quickly denied by the State Department. Recognizing the sensitivity of recording conversations without the consent of the other party, Kissinger had tried to keep the transcripts secret as long as he could, claiming them as his personal property. By the end of 1976, journalists had learned more about the telcons. Media outcry and a threatened lawsuit by historians prompted Kissinger to quick action: he donated the documents to the Library of Congress where they would be out of reach of FOIA requests.

Most of the documents posted today come from the records of State Department Legal Adviser Monroe Leigh, who held the position during 1975-1977. To get access to the 17 cartons of Leigh’s records, the National Security Archive made an Indexing on Demand request to NARA’s National Declassification Center, which completed their final processing and opened them in November 2023.

Even as many important collections remain unavailable—Eagleburger’s official files are still held at State, while Kissinger’s papers remain closed—these new documents from the Leigh collection provide fascinating insights on Kissinger’s initial efforts to keep the telcons secret.

READ THE DOCUMENTSTHE NATIONAL SECURITY ARCHIVE is an independent non-governmental research institute and library located at The George Washington University in Washington, D.C. The Archive collects and publishes declassified documents acquired through the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA). A tax-exempt public charity, the Archive receives no U.S. government funding; its budget is supported by publication royalties and donations from foundations and individuals.

Leave a comment