Monday, 26 May 2025 — Red Flag – Socialist Notes

Of a place I cannot entirely recall

A memory of Gummidipundi refugee camp, north of Chennai, haunts me. In dim light, a young(ish) man, missing one of his limbs, sits on the concrete floor in a brick shack. The roof is thatched, or maybe it’s concrete sheets, perhaps asbestos. Hopelessness has eaten away at his eyes; not even a hint of anticipation animates their gaze. That’s what sticks. His demeanour doesn’t shift. It’s as though nothing will ever change, a barren future seemingly already written.

Yet my notebooks and photos show no record of ever being here. I’ve gone through everything that I retained from the trip. That I now can’t even conjure his name feels callous. Have I lost my notes? Or did I put the pencil away out of a desire not to compromise what was left of his dignity? Could I not bring myself to record anything? Perhaps I was asked not to, as sometimes happens in these circumstances.

I can’t recall. But it must have been something—the memory is etched, the scene too real to be a concoction. It was dusk, or just past. A circle of people sat in the room, each on the floor, all listening, and with their own story that would not be told. Not to me, at least.

Why can’t I remember his name? And was it his arm or his leg, missing from the elbow or the knee? All I can picture are those eyes, brown and sullen. Full of life, but not the life anyone would long for. They were still young, though; age didn’t take away their sparkle. Sometimes when I’m drinking alone, chain smoking menthols, his face appears, distant, staring at the floor.

It’s more than half a decade ago now. We were visiting refugee camps across Tamil Nadu. A long day of interviews had left us feeling harried. Or was it just me, with a train to catch? Maybe it was the cups of tea and their attendant build-up of caffeine across hours.

Even if I’d jotted the usual way on paper or recorded the conversations on the phone, it would have helped only so much: you cannot interview someone only once if you want the truth. I didn’t understand that at the time. But having previously been in Sri Lanka and Indonesia with former Tamil Tiger cadres and their families, I should have.

Our memories often contain many contradictions. They have been reworked a thousand times—to make sense of them, to fit them into a meaningful narrative—before being recounted to another person. The translator, too, filters and interprets the responses. The subject and the translator also try to decipher what you want to hear, thereby censoring themselves, if only for brevity. That, of course, is generous. But the omissions can also strain the truth. By the time you realise, it’s too late. You’ve moved on, out of the town, the province, the country.

Hegel wrote that impatience demands the impossible: attaining the end without the means. He might also have said that laziness often demands likewise. Ultimately, it is just plain lazy to sit with someone for a couple of hours and think that you can divine their life’s worth. That’s why, years later, you wouldn’t remember their name, or which of their limbs was amputated, or how exactly they ended up in a refugee camp in a foreign country.

These thoughts have eaten away at me these last few years. Before the pandemic, I put together a book that received generous reviews, no doubt in part because it had noble intentions: to illuminate a people’s struggle by reconstructing the life of one of its protagonists. But I now view it with a sense of unease. How impatient, or lazy, was the reconstruction? How timid were my interrogations? Not a few people put targets on their backs by speaking openly or by navigating me through the military occupation in Tamil Eelam or through the Indian camps potentially littered with spies augmenting their rations by providing information to the authorities. How much did the writing repay them for those risks? Not near enough, if I’m to be honest.

Moreover, how does anyone get it right? If the past is what really happened, and history is our record and interpretation of that reality, then, arguably, most writing should be history. But so much of the past feels like it is already walled off, but for the effort to penetrate the memories of its witnesses. So the effort matters a great deal.

I’ve probably opened myself up to ridicule here—they probably explain this stuff in first-year university courses on how to do history. It’s to my disadvantage that I wasn’t taught such things and learnt only through stuffing it. Either way, there’s a lesson. And while this might all seem a little self-indulgent, there’s a broader point.

For three decades, beginning in 1983, more than 300,000 Sri Lankan Tamils sought refuge in Tamil Nadu, India’s southernmost state, as the national liberation war raged across the Palk Strait, led by the Tamil Tigers. More than fifteen years after the Sri Lankan armed forces emerged victorious, perhaps 100,000 of Sri Lanka’s Tamil-speaking minority remain in India.

The refugees are tolerated, but they have few rights. The majority, about 60,000, reside in more than 100 camps, where they are under the surveillance of Q Branch, the intelligence wing of the Tamil Nadu police, founded initially to deal with the Naxalite movement and later refashioned to tackle Sri Lankan Tamil militant groups operating in the state.

Many of these stateless people were born into a country that rejected them, but they have little future in the land that they, their parents or their grandparents fled. There are around 1,000 families in Gummidipundi alone.

Over the years, we—Red Flag, the Tamil Refugee Council, and many other refugee rights activists in Australia—tried to bring attention to the national liberation movement and its aftershocks. My friends and comrades Lavanya Thevaraja and Aran Mylvaganam, along with others whose names can’t be mentioned here, have done a great deal to bring attention to the situation(s), and to the remnants of the Tigers scattered throughout Asia, some of whom still survive in Sri Lanka. I tried to help as well.

It makes sense to interrogate the efforts and consider whether more could have been done in the reporting. Perhaps I’ll soon get another chance. If so, you’d hope we learned a few lessons from previous attempts. And maybe some of these thoughts will be useful for the next set of activists who attempt to write history, be it of a rebellion or a local trade union strike.

For what it’s worth, it comes down to this: stay longer, listen more intently, and clarify. Stay for a few days, depending on where you are. Eat, drink and play games. Watch. Listen to what’s being said when you aren’t asking a question. Then come back to clarify some more. My feeling is that this advice holds whether it’s a refugee camp or a working-class household in the suburbs. Think long and hard about how you can do justice to the story you are attempting to tell.

Above all, remember. Forgetting is agony. It’s a torment. More than that, it is an injustice. We need to hold on to what really happened—wherever it happened—as best we can.

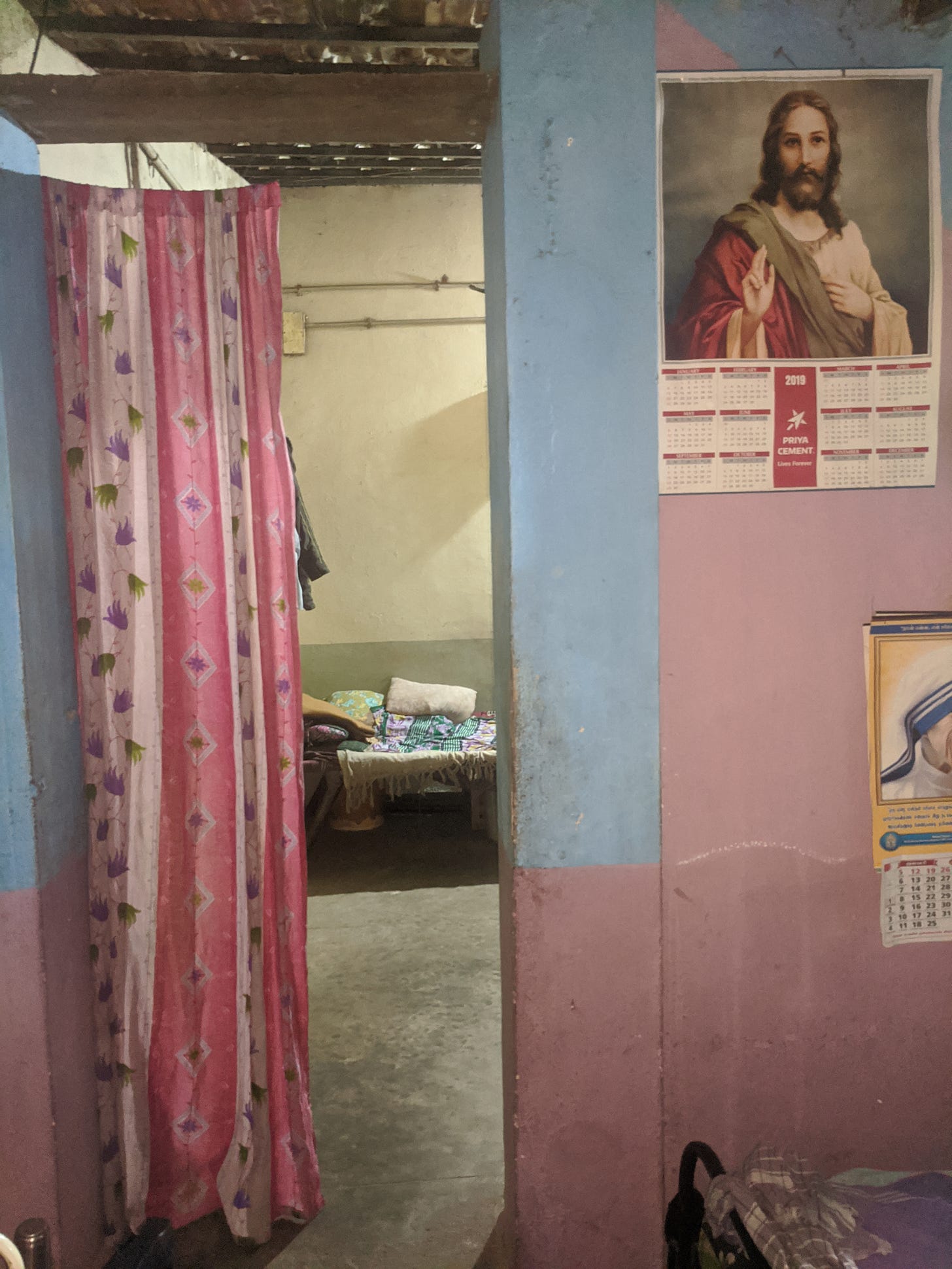

The photo below is from Vellore refugee camp, Tamil Nadu, where Lavanya (not pictured) was raised. Aran is on the left, taking the shot. None of the men were members of the Tigers. I think all of them were born in India. But that’s another detail that escapes my memory. The main thing is that too many people, all over the world—with all its riches—still don’t have a place they can yet really call home.

Leave a comment