Monday, 25 August 2025 — Geopolitics & Climate Change

This is a review of a chapter in the edited volume “A History of American Literature and Culture of the First World War” that Alexander Anievas has made available online here. The introductory paragraph:

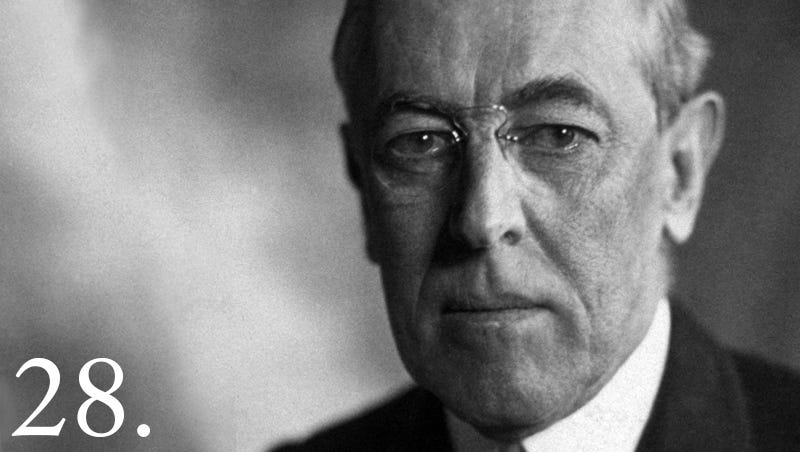

This chapter explores the mutually reinforcing transformations in American state-society and foreign relations engendered by the First World War and its aftermath. The post–Second World War period is typically seen as the moment of decisive rupture in the history of US foreign relations with the establishment of American hegemony and the making of the Cold War. This chapter problematizes the notion of such a sharp break by highlighting the continuities between the two postwar periods contextualized within the longue durée of American state-formation and the emergence of a racialized anticommunism. In particular it examines the ideological-political and cultural antecedents to Woodrow Wilson’s liberal internationalist project and its relationship to the defense of white supremacy at home and abroad. US hegemonic practices were constituted in and through the racial articulation of an anticommunist “common sense” defined by a militantly normative Americanism with roots in the First World War and its immediate aftermath.

Situating the beginning of the Cold War properly at the end of World War 1, and the basis of Wilson’s “liberal internationalism” in a racialized anti-communism that became embedded in the US hegemonic culture. Wilson, as recently belatedly recognized in mainstream US culture, was a racist bigot. He was also a fascist, see American Midnight by Hochschild, a fact that will never be accepted in US hegemonic culture.

As Anievas notes, at the dawn of WW1 in 1914 the white European colonial powers extended their control over 84% of the globe’s land surface. It could be said to be the zenith of white European imperial dominance. With the main driver of the world war being the struggle between imperial powers for colonial spoils, with Africa having been split between those power only the in the preceding few decades. And democracy at home attenuated by the realities of racialized imperial brutality and exploitation abraod.

Du Bois explained how modern imperialism wore a “democratic face” at home while turning “a visage of stern and unyielding autocracy toward its darker colonies.” Yet the denial of democracy in the colonies hindered its complete realization in the European metropole. “It is this,” Du Bois suggested, “that makes the color problem and the labor problem to so great an extent two sides of the same human tangle” (442). In Du Bois’s view anti-colonial struggles were inextricable from the emancipation of labor from capitalist exploitation

The threat of communism was very much seen in racialized terms, as it rejected the white supremacy with which the white ruling class bound the rest of the white population to itself rather than poor and working class whites seeing themselves and Black people as natural allies against the ruling class that exploited them both. A tactic used very much in the Republican “Southern Strategy” of the 1960s and today with the nativist, racist and xenophobic cultural tropes against Latinos, Arabs and non-white immigrants.

Racializations of the communist threat were found at the highest echelons of US policymaking circles. From President Wilson and Robert Lansing, his Secretary of State from 1915 to 1920, and later to FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover and Cold War “architect” George F. Kennan, racial anticommunist assumptions and practices suffused the American state

As the author states:

Even as the history of international relations is embedded in a history of race, then, so too is the history of anticommunism. The global color line cut across the Cold War, dividing “white” from “black,” “brown,” “yellow,” and “Red” along blurred and often shifting ideo-political registers. “Being a white person or person of color,” Heonik Kwon notes, “was a major determining factor for an individual’s life career for a significant part of the past century, but so was the relatively novel color classifications of being ‘Red’ or ‘not Red’ in many corners of the world including the United States and South Africa” (38). The inculcation of anticommunism with racial signification was a potent force in the ideological and repressive repertoire of the American state and its counter-subversive practices. A distinctly “racial practice” embedded within and constitutive of a broader “common sense” (R. Seymour), it policed dissent at home and projected US imperial interests abroad.

The first “Red” socialist population was the Amerindian one that was subjected to ethnic cleansing and genocide in a process envisaged by white elites as a “regeneration through violence”.

War against the Amerindians offered the “symbolic surrogate for a range of domestic social and political conflicts”: a way of redirecting class conflict outward against the “Indian savage” and diffusing social tensions. US foreign relations were in turn conceived through the prism of a “grand-scale Indian war” whereby “progress was achieved through regenerative wars against a primitive racial enemy”.

With the first “Reds” defeated with the closure of the “frontier”, the US ruling class could both look abroad for new conquests and also required an external enemy to focus working class attention away from the ruling class exploitation of the average American. Especially with the 1873 to 1896 Long Depression that was a time of great labour and small farmer agitation in parallel with the development of huge corporate entities, during which “the entwinement of racialized imperialism and class conflict became ever more marked”. Socialism was imbued with both racial and foreign characteristics by the hegemonic culture reflected in the media and state policies and announcements. The Soviet communists were likened to godless savages in the same way that the Amerindians and Blacks had been; from a “half-Asiatic” and “backward” Russia . At home “subversives” were regularly claimed to be inciting the Black community, when the period was in fact one of extensive white violence against the Black community.

In parallel to the late and post-WW1 state fascism, including what could be seen as the first “brownshirts” the American Defence League directed by the precursor to the FBI, was the resurrection of racist terror campaigns with the Klu Klux Klan (fully supported by the racist president who is quoted in the infamous racist film “Birth of a Nation”). The state, and the ruling class that directed it, pulled every lever of nativism, racism, xenophobia, populist militarism and the branding of opponents as “aliens” and “radicals” and “radicalized minorities” in their fight to maintain power during the challenges to their rule.

Hoover charged the communists with having “done a vast amount of evil damage by carrying doctrines of race revolt and the poison of Bolshevism to the Negroes” … During his League of Nations tour, Wilson went so far as to attack opposition from ethnic Americans as both “un-American” and violent, arguing that “any man who carries a hyphen about him carries a dagger … ready to plunge into the vitals of this republic whenever he gets the chance”

For the white supremacist Wilson, the natural global order was one of the civilized Anglo-Saxons teaching the other ethnic populations of the Earth how to be civilized; national sovereignty and determination being a Eurocentric privilege. Echoing the recent statements of an EU foreign representative about the European “garden” and “jungle” of the non-Europeans; showing how prevalent such attitudes still are, if usually better hidden, among Western elites. Socialism called for national determination for all peoples, upsetting the basis of Western colonialism and the self-image of the colonial Anglo-Saxons. As well of course, upsetting the “natural” class order of Western societies. When direct intervention failed to defeat the Soviets, a cordon sanitaire was erected to keep their dangerous ideas out and to keep the Soviet state weak. The real beginning of the Cold War, that enjoyed a respite during part of the 1930s and WW2. Wilson’s celebrated “Liberal International Order” was simply a culturally acceptable and indirect call for the continued dominance of the Anglo-Saxon elites over world affairs; continued into the present.

At the moment of its inception, then, America’s “Wilsonian century” was predicated on a form of anticommunism permeated and infused with racial undertones that became a key – albeit highly contradictory – pillar of US hegemony after 1945. And, in this respect, the reproduction and buttressing of racial hierarchy and white supremacy at home was a central foundation for the establishment and expansion of US “liberal” hegemony abroad.

This is why the success of the Chinese, of the Persians and the Slav Russians is so threatening to even the most basic conceptions of the world that the Anglo-Saxon elites (and the new “whites” and co-opted racial elites) hold, one of equality between ethnic groups rather than dominance and subservience. Or even worse, the dominance of non-white elites such as the Chinese. These are the racial undertones of the current geopolitical environment

Leave a comment