4 March 2020 — Zero Hedge

Summary

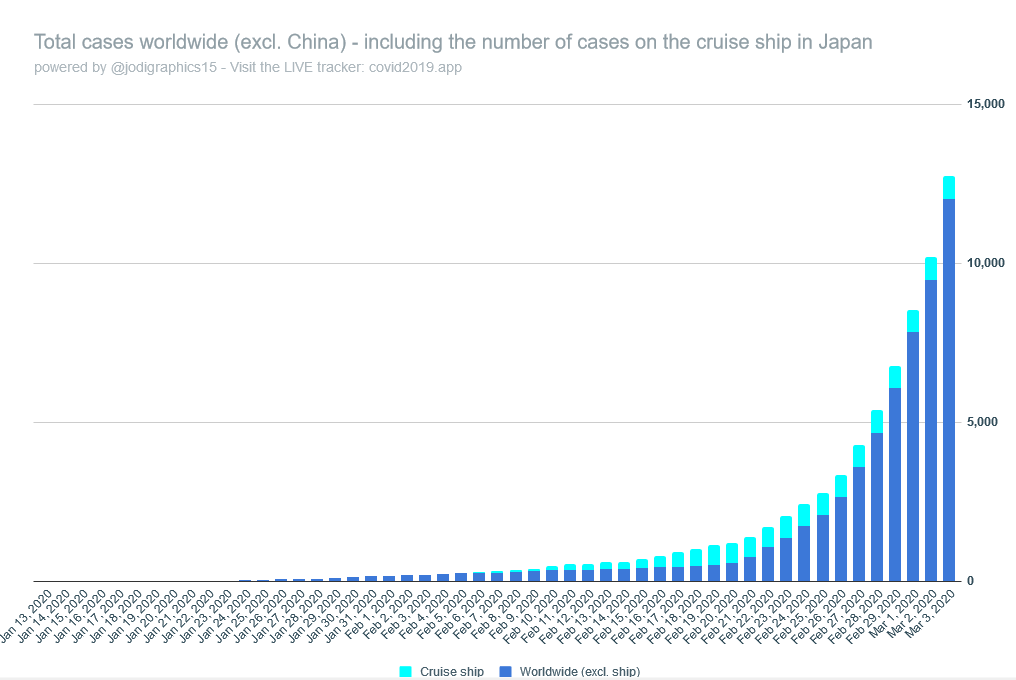

- Covid-19 has broken out of China and become a key global concern: most countries are now preparing for a serious virus epidemic.

- All governments are faced with a series of unpalatable options over their next steps – yet all end with serious economic damage.

- As a counterweight, we will see a reliance on several types of fiscal and monetary policy response: the conventional, the unconventional, and the ‘unconversational’ – steps that would not even have been talked about until very recently.

- “The Conventional” response is already well underway with the RBA cutting rates 25bp to 0.50% and the Fed making an emergency cut of 50bp to takes Fed Funds to 1.25%: this was the first 50bp cut and the first out-of-meeting move since the Global Financial Crisis.

- However, conventional policy is arguably of little impact, as initial reactions to the Fed surprise show – and the same is just as true for unconventional policy.

- This takes us rapidly towards market conversations about the ‘unconversational’.

It’s getting “The Ugly”

A few weeks ago we published a special report on Covid-19 which projected four scenarios for the virus’s economic and market impact: “The Bad”, “The Worse”, “The Ugly”, and “The Unthinkable”.

“The Bad” scenario was based on the assumption that there would be virus containment within a few weeks within China, with limited spread to other countries. This was already seen as nastier than the market was pricing for, with Chinese 2020 GDP growth reduced by -0.5% to -1.0%, and global GDP by -0.2 percentage points. This was our base case at the time.

“The Worse” scenario envisaged an ongoing Chinese lockdown and the virus spreading to parts of ASEAN. This would have a larger regional and global impact. Chinese GDP growth was seen grinding to a halt, with a severe slowdown in ASEAN too, and significant global supply-chain disruptions meaning a global recession closer to the likes of 2008/09.

“The Ugly” scenario envisaged that the US, UK, and Europe were infected too. Naturally, this implied a deep global recession.

“The Unthinkable” was a real-life version of a Hollywood movie.

At time of writing, major virus outbreaks in South Korea, Iran, and Italy, as well official warnings from the rest of Europe, the UK, the US, and Australia, show us that we risk entering into “The Ugly” scenario and that a deep global recession may be inevitable. (See Figure 1.)

What is to be done?

As a result, attention is rightly turning to that old Leninist question: what is to be done? Most developed economies have now set up government virus crisis teams (COBRA in the UK, a new unit under Vice-President Pence in the US, for example). The question is, what can they do? The answers are unpalatable. Although the messaging and rhetoric varies in each location, there are logically only three basic options:

Do nothing and tell people all is well.

This option was tried at first in most Western countries – as evidenced by the lack of serious virus preparation until recently. However, Iran–where the total death toll is unclear but the virus appears to have taken a terrible toll already–is a graphic illustration that telling people all is well is not an effective strategy. The Iranian economy, already struggling under sanctions, has understandably suffered another huge blow as people panic and stay at home. As we noted in our previous report, both supply and demand have collapsed in tandem.

Allow business as usual while telling people to prepare

For now this is still the option being pursued by Western countries, with normal movement still allowed – indeed, encouraged. Yes, there are some restrictions in place–France has banned indoor gatherings of more than 5,000 people–but generally people and businesses are free to operate as usual. The problem is that even so many people are nonetheless reacting with fear, cancelling holidays, stopping travel and having meals out, and/or panic buying and hoarding essentials such as pasta and toilet rolls, as well as hand sanitizer and face masks. In short, the economy is already taking a major virus hit anyway – look at airlines as an indicator.

Institute China-style lockdowns.

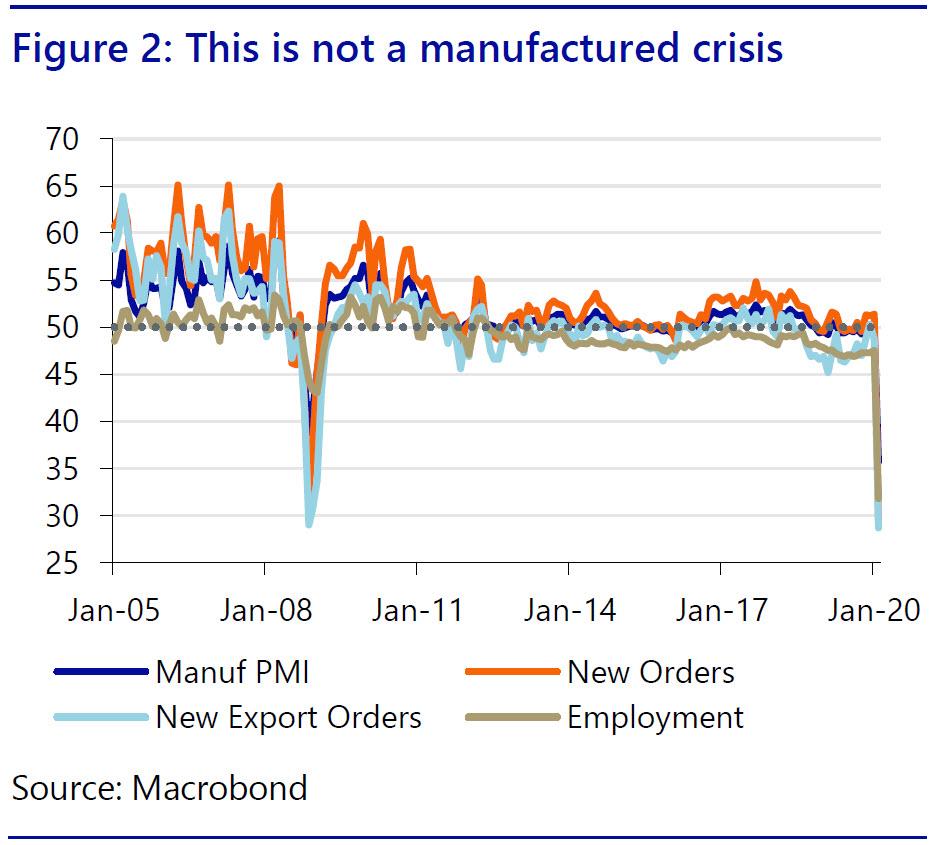

So far these steps have only been taken in specific virus hotspots in developed economies, for example Northern Italy. However, they are clearly ready to be more widely used if needed. Indeed, on 3 March the UK stated draconian action could be seen in its official worst-case scenario involving 1 in 5 of the population being infected and ill, requiring major cities to be locked down, public transport to be stopped, schools to close, workers to be told to work from home, the army on the streets, and the police told only to deal with serious crimes. Naturally, the impact on the economy of such a lockdown would be dramatic – as has been seen in the collapse in the Chinese manufacturing and services PMIs in February, the first real chance we have had to look at relevant official data since Covid-19 broke out. (See Figure 2.) However, there is broad recognition that the steps China took have played a key role in sharply reducing the number of new virus infections being seen in recent weeks. In other words, lockdowns do seem to work – and without them, this would already be a truly global pandemic.

The other key thing to note, however, is that whichever of the three options a government takes, the outcome is major damage to the economy.

Do nothing, and the economy is hit by the virus; act incrementally and a virus outbreak is likely to be larger – and the public to panic anyway, hitting the economy; lockdown the economy and be *guaranteed* a deep downturn.

Moreover, even if the last option were chosen, such action still needs to be coordinated between countries to be effective – yet effective international coordination can be very difficult to achieve, seeing countries resort to unilateral action instead.

For example, there is no use locking down one’s own economy, as in China’s case, if arrivals from another country that has not been taking virus precautions, like Iran, are free to enter and spread infection once again. Tellingly, China, the origin of Covid-19, is now putting travel restrictions in place for visitors from some other countries, such as Iran, after vociferously complaining that its own citizens were discriminated against by other states when it was still seeing the heaviest phase of the virus impact.

Slow burn not V-shape?

One other thing needs to be made clear, but which not many are expressing: at this stage, and regardless of the strategy pursued, there is a real risk that the virus will spread globally. In which case, the best that even quarantine measures can realistically hope to achieve is to spread out the impact of the virus so that not everyone gets sick at once, so reducing the strain on healthcare systems as well as economies. Yet this also means that this cannot be a quickly-resolved “V-shape” issue, but rather a slower burn with longer-lasting economic effects. The British government is now transparently assuming that this will be at least as 12-week cycle, hopefully beginning to be under control properly by June.

It is hard to square such thoughts with Bank of England Governor Carney’s recent message that in the UK Covid-19 will cause economic “disruption and not destruction”. For one, we have to stress that hysteresis is as important as hysteria: the longer the crisis lingers, either because of government actions or regardless of them, the deeper the economic damage that will be done on many fronts: how will many millions of the self-employed and small businesses owners, mortgage holders and credit-card borrowers survive for three months with little or no income. The impact of this crisis, even if managed well, may last well beyond what cynics would usually assume when dismissing panic-filled newspaper headlines.

Moreover, three months is an estimate. Even as UK (and US and European) summer eventually arrives, hopefully reducing the virus’s impact, it will be winter in Latin America and Sub-Saharan Africa, Australia, and New Zealand, all of whom have virus cases already, and the first two of which may not be in a positon to properly monitor or control going forwards. As such, unless economic connectivity between the northern and southern hemispheres is severed, doing even more damage, the risk is that there will be a fresh avenue of potential Covid-19 infection awaiting when summer turns back into autumn again. This is exactly what happened with the Spanish Flu in 1918-19, as we showed in another recent virus special report (“Fear and Trembling”). Slow-burn, not V-shape once again.

Of course, the nearest-term concern is with China as it tries to get hundreds of millions of workers back to work again without seeing a V-shape in virus infections too. Can this be done, or will it illustrate the damned-if-you-do, damned-if-you-don’t nature of this crisis?

So what IS to be done then?

The above is the key question and has been made all the more timely by the fact that 3 March saw an unprecedented gathering of the G7 and major central banks to discuss Covid-19 and the possible coordinated policy response. Expectations were high given how rare such meetings are: the outcome was pure disappointment, with the brief press release stating:

“We, G7 Finance Ministers and Central Bank Governors, are closely monitoring the spread of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) and its impact on markets and economic conditions.

Given the potential impacts of COVID-19 on global growth, we reaffirm our commitment to use all appropriate policy tools to achieve strong, sustainable growth and safeguard against downside risks. Alongside strengthening efforts to expand health services, G7 finance ministers are ready to take actions, including fiscal measures where appropriate, to aid in the response to the virus and support the economy during this phase. G7 central banks will continue to fulfill their mandates, thus supporting price stability and economic growth while maintaining the resilience of the financial system.

We welcome that the International Monetary Fund, the World Bank, and other international financial institutions stand ready to help member countries address the human tragedy and economic challenge posed by COVID-19 through the use of their available instruments to the fullest extent possible.

G7 Finance Ministers and Central Bank Governors stand ready to cooperate further on timely and effective measures.”

Measure for measures

So what can the G7 actually do? Arguably, their possible “effective measures” above and beyond direct virus-fighting steps again come down to three broad areas: The Conventional; The Unconventional; and The “Unconversational” – things that were simply unspeakable in official circles until recently. Yet these three options all still sit within the normal axis of fiscal and monetary policy options.

Frisky Fiscal

The G7 statement openly mentioned “fiscal measures, where appropriate”. This suggests that there is no broad agreement on the need for fiscal stimulus right now. The US, with its past Trump tax cuts, and the UK, with its recent shift to a “leveling up” infrastructure budget, have already moved decisively towards larger fiscal deficits – but this can actually limit the extent to which further stimulus can be introduced above and beyond the automatic stabilizer effect that will naturally occur as the economy and tax-take decline in tandem. Moreover, in the Eurozone the room for fiscal maneuver is far more constrained by treaty, in Japan’s case by the government’s insistence on trying to reduce the fiscal deficit (given Covid-19, the timing of Japan’s last sales tax hike could not have been worse!), and in Australia’s case the fiscal constraint is also strong, even if it is entirely self-imposed.

However, there is a more general criticism of fiscal policy: it is slow to take effect, and in the case of the virus is unlikely to be of much short-term use. If consumers are locked away at home, what good does it do to start to build a new railway like High Speed 2 in the UK, for example? In some cases, one can make direct transfers to households or firms, such as the Trump tax cuts – but these would need to be better targeted at lower and middle-income groups and/or SMEs than the tax cuts seen to date in the US. At the same time, if one is bunkered away in fear of a virus, will a few extra dollars in one’s pocket incentivize going out to spend? Unlikely. That said, a liquidity-constrained SME could be hugely grateful for an emergency cash injection, especially if this can be used to pay salaries and prevent a domino effect of unemployment and/or demand destruction.

Naturally, China is taking the lead fiscally. It has already introduced tax cuts to try to offset the effects of Covid-19, and its semi-official Global Times has stated Beijing may be forced to embark on a major stimulus package larger than the CNY4 trillion (USD574bn) infrastructure stimulus package seen back in the 2008 financial crisis–“despite the side effects”–should the economic damage from Covid-19 prove too great. Understand that back in 2008 China’s GDP was USD4.7 trillion vs. USD14.3 trillion today, so if they imply a stimulus package larger as a percentage of GDP, which is not clear, then we are potentially talking about USD2.0 trillion stimulus package.

For China, that kind of thinking, incredibly, is still taken as within the conventional. In developed economies, it would be totally unconventional, as it implies a war-time level of fiscal deficit – but that does not mean that the political winds will not blow in that direction too; healthcare may take precedence over bombs, or over infrastructure, but the economic impact of massive deficit spending would be just as positive for developed economies.

Naturally, when talking of large-scale fiscal packages when public debt and/or fiscal deficits are already very high, we go beyond what was once the conventional and even the unconventional; we enter the realm of the ‘unconversational’, and of fiscal-monetary policy cooperation, or Modern Monetary Theory. We have discussed this several times in recent years (see here for example): might Covid-19 prove the political launch-pad for it outside China?

Mainly Monetary

Mainly Monetary

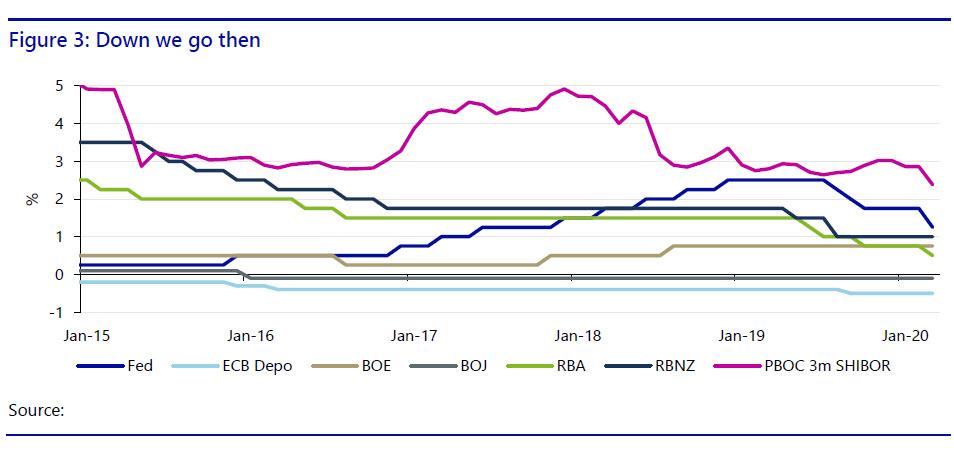

Central bank governors of course “stand ready”, a message that the Fed, ECB, BOE, and the PBOC, have already made clear to the public and markets. Conventionally, this first means rate cuts, even allowing for the very low level of rates to start with. These are already arriving:

The PBOC got in first, reducing their new benchmark 1-year Loan Prime Rate (LPR) by 10bp to 4.05%, while the fall in 3-month SHIBOR has been even steeper;

Other Asian central banks have been cutting for some time already, with Malaysia cutting 25bp on 3 March, for example. That said, the Bank of Korea (BOK) opted not to cut 25bp as expected last week, even though Korea has been very badly hit by Covid-19, as it did not see lower rates as an effective instrument to fight a virus (a point we shall return to);

The RBA were developed market trend-setters in cutting their overnight cash rate 25bp at their March meeting, taking the OCR to a new record low of just 0.50% – overtly over concerns about the supposedly short-term impact of Covid-19 on the services sector; and

this was then eclipsed by the Fed cutting rates 50bp at an inter-meeting move for the first time since the Global Financial Crisis (See Figure 3.)

With the Fed action in particular, the rates flood gates have now opened even if rates are already close to zero, or below: the BOC, BOE and BOJ, to say nothing of other smaller global central banks, are certain to follow rapidly. Yet as with tax cuts, what use is a lower cost of borrowing if there is no supply and no demand? If you afraid to go and eat in a restaurant for fear of infection and possible illness or even death, then a slightly cheaper mortgage-loan rate will not really change your mind. This is the same fundamental problem that we already see with ultra-low rates and business investment: it’s ultra-cheap to borrow, but why risk it when there is no demand? Tellingly, the immediate market reaction to the Fed’s “bazooka” 50bp cut was to see both equities and yields drop sharply – and at both ends of the curve, with 10-year yields now decisively lower than the psychological and unprecedented 1% level.

So what then? At this point, the conventional must become unconventional. We already know what this “emergency” policy toolkit looks like: central bank asset purchases (i.e., QE) and asset swaps (reverse repos). Both of these are already in large-scale use, and both of them are likely to see even greater escalation in scale and geographical breadth: Australia will join the QE club, for example.

Of course, as we have argued repeatedly in various reports for years, even in a ‘healthy’–if structurally distorted–economy, QE has failed to generate sustainable, equitable growth or inflation. In an economy about to suffer from Covid-19, it will be even less effective. Reverse repo is also just papering over cracks in asset quality rather than addressing fundamentals.

Yet if new QE goes into government bond purchases to fund productive fiscal spending that boosts the economy, so much the better; however, that takes us from the unconventional to the ‘unconversational’.

Purely political

Apart from the fiscal and the monetary, one needs to recall that all governments have a third channel for policy measures that can also be considered very “unconversational” – the Purely Political. We tend to think of real power sitting with central banks and little with our elected officials: this overlooks the fact that the elected officials gave their power away – and can take it back again.

The struggle against Covid-19 is, quite naturally, already being portrayed as a ‘battle’ or a ‘war’, and during wars politics always takes precedence over business (and markets) as usual. If that kind of ‘kitchen sink’ strategy was available for GFC 2008-09, why should it not be with Covid-19?

We have already seen the state impose lockdowns in various regions of various countries, and/or international travel bans totally at odd with traditional freedom of movement: more seem very likely.

In France the government has requisitioned protective masks, and the US is contemplating using Korean-war era legislation to compel the production of anti-virus equipment: again, this is completely normal in present circumstances – and completely opposite to what the Western political-economy trend has been for decades. If the virus outbreak gets worse, one could easily imagine the government acting even more significantly via price controls or rationing of key goods, or by compelling companies to act in certain ways. Temporary nationalizations may even be required. These steps would no doubt be widely supported by the public if it helps prevent profiteering and better health outcomes.

Financially, given the huge blow that airlines and other service-sector firms are likely to suffer, we are also certain to see state aid and/or bailouts to key firms, even if this is technically illegal in some countries currently. We might we also face some temporary quasi-nationalisations once again, as during 2008-09.

Meanwhile, companies will be told to keep paying workers regardless of their cash-flow. In turn, banks will be leaned on to maintain credit lines to businesses and households, or to even extend debt facilities despite it running contrary to usual risk metrics. China is already leading the way here. Indeed, as in China we could also see a possible suspension of mark-to-market pricing for some financial assets or, copying their experience of 2015, a ban on short selling of stocks to try to ensure that this crisis does not become a full-blown financial calamity. It cannot be ruled out.

In short, almost every key part of the economy could, in the worst case, be subject to some form of state interference and prevention of price discovery. That is exactly what happens during wars – which as Von Clausewitz infamously quipped, are an extension of politics by other means.

Again this would likely be popular with much of the public, no doubt, and perhaps even with markets if it saves them from any major downside risks. Yet some will also quote pithy US journalist H L Mencken: “The urge to save humanity is almost always only a false-face for the urge to rule it.” Extricating the state from markets after the virus has passed may prove difficult, especially when the pre-virus economy already had so many pressing socio-economic imbalances to deal with.

But that’s an “unconversation” for another day. Let’s get through Covid-19 safely first.

Source: @jodigraphics15

Source: @jodigraphics15