13 May 2021 — Consortium News

The defence counsel has reasonably criticized the decision to impose a prison sentence, writes Alexander Mercouris.

in London

Special to Consortium News

The troubling conviction of former British diplomat Craig Murray for contempt of court in connection with his coverage of the prosecution of the prominent Scottish nationalist politician Alex Salmond on sexual assault charges has now produced an equally troubling sentence by a tribunal of the Scottish High Court of eight months in prison for Murray.

The troubling conviction of former British diplomat Craig Murray for contempt of court in connection with his coverage of the prosecution of the prominent Scottish nationalist politician Alex Salmond on sexual assault charges has now produced an equally troubling sentence by a tribunal of the Scottish High Court of eight months in prison for Murray.

In my two previous letters on the Murray case, I discussed the political background and legal issues, in particular the way in which the so-called objective test, which the Court was purporting to apply when assessing Murray’s reporting, threatened to make media reporting of a case such as Salmond’s all but impossible in any meaningful sense.

The Court said that according to the “objective test,” it did not actually matter whether reporting of a case did in fact result in the public identification of a witness or complainant who had made sexual assault allegations against a defendant. Nor did it matter if the reporter who wrote about the Salmond trial had any intention that his or her report would lead to the public identification of a witness or complainant. It sufficed for the reporter to be in contempt of court, according to the Court, if a witness or complainant might conceivably be identified, including by persons who know them intimately.

Given such a test I do not see how balanced reporting of a case like the one brought against Salmond (which ended in acquittal) would be possible in practical terms. It does not seem possible to provide an article that reported the case fully and properly but which also did not report at least some facts which some people might say, rightly or wrongly, could conceivably cause the identification by someone of a witness or complainant.

Craig Murray

Craig Murray

Given that the defendant does not enjoy similar protections, that seems to me to contradict the overriding legal and human rights obligation for equal and balanced justice, which requires that trials, save in exceptional circumstances, be conducted openly, and be reported in a full and balanced way.

In saying this it is essential to stress that the protection of witnesses and complainants in sexual assault cases is a paramount priority, and that the need to take steps to provide them with protection by securing their anonymity is not at issue. However, to use this obligation to prevent balanced reporting of a case, especially one like Salmond’s, which had important public and political implications, seems to me to go too far and looks oppressive. It appears to extinguish the right to a fair and open trial, which can only be secured by fair and balanced reporting. Inevitably that begs the question of whether the true intention of the Court’s order of anonymity was less to protect witnesses and complainants and more to prevent the balanced reporting of the case.

Here it is important to say that proportionality is a fundamental principle of human rights law. It seems to me that the Court’s “objective test” risks offending against the principle of proportionality, to the point where the right to fair and equal justice is extinguished.

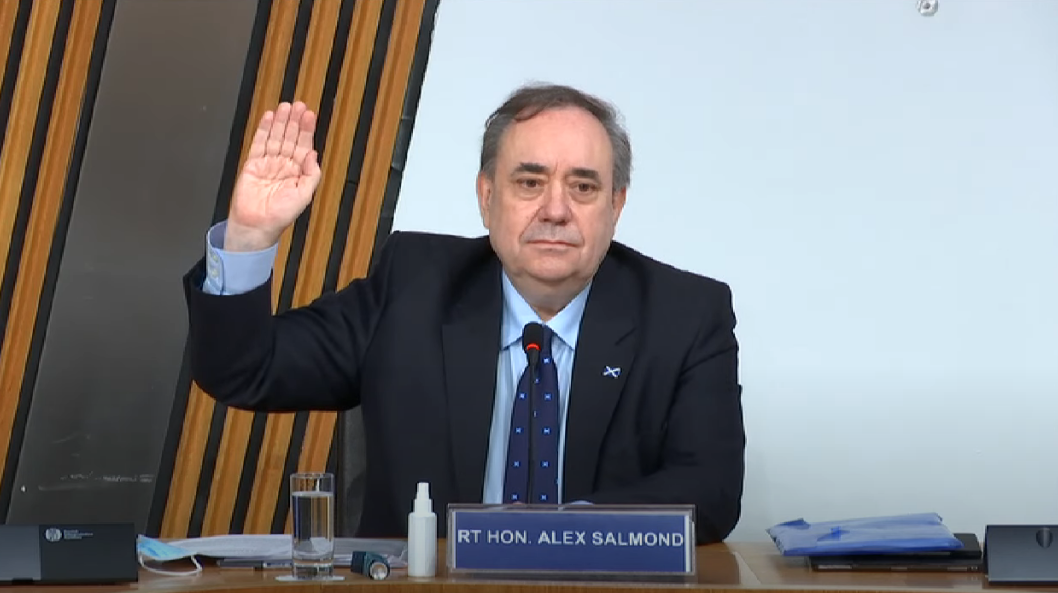

Alex Salmond preparing to give evidence to the Committee on the Scottish Government Handling of Harassment Complaints, Feb. 26. (Scottish Parliament, Wikimedia Commons)

Alex Salmond preparing to give evidence to the Committee on the Scottish Government Handling of Harassment Complaints, Feb. 26. (Scottish Parliament, Wikimedia Commons)

In sentencing Murray, it is possible that the Court was alive to these concerns because in its sentencing comments it appeared to have moved away from a strict application of the “objective test.” Instead, it spoke as if Murray by his reporting had actually intended that the identities of the complainers in Salmond’s case should be revealed. Murray’s breach of orders conferring anonymity on the complainants was according to the Court’s sentencing comments not inadvertent. On the contrary, the Court said it was brazenly willful. Indeed, Judge Lady Dorrian spoke of Murray actually “relishing” the possibility that the identities of the complainants might be revealed as a result of his reporting.

This has introduced an element of malice into Murray’s reporting which to my knowledge had not been mentioned before.

Up to a Higher Court

It will be for the Supreme Court to decide whether the evidence that was presented to the Court does indeed prove such an element of malice on Murray’s part. In my opinion the evidence does not show it. Of course, Murray, in his affidavit evidence, denies that he had any intention or desire to reveal the identities of the complainants. Instead, he goes to great length to explain the painstaking steps he took to avoid the “jigsaw” identification of the complainants. If true, that would mean that the malice the Court claims as the reason for his actions never existed.

At the very least I would have expected the Court to have held back from making sweeping conclusions about his intentions and desires without first hearing from him under examination and on oath on the witness stand during his trial. Nothing like that of course happened. Perhaps it is not the practice to do that in cases of this kind in Scotland. However, it is another feature of the case that is troubling.

Having said that Murray’s actions were malicious, the Court proceeded to sentence him to prison.

This despite the fact that Murray is a person of good character, who is in his sixties and in poor health, and who has a family which includes two young children, one of whom is a baby only a few months old.

Murray’s defence counsel has reasonably criticised the Court’s decision to impose a prison sentence as being “harsh to the point of being disproportionate.”

The imposition of a prison sentence in a case of this sort is inevitably going to foster claims by some people that call into question the authorities’ good faith in bringing the case. Some will no doubt point to the prison sentence as “proof” that the real purpose of the case was not to protect the complainants or to uphold the law, but rather to punish Murray, who has been a thorn in the side of the establishment, both in London and in Edinburgh, for many years now.

I have seen no evidence that this is so, and the Scottish authorities will of course strenuously deny it. There are no doubt people who make these sort of claims regardless of the outcome of the case. However, the fact remains that the imposition of this prison sentence will make these claims more prevalent, and perhaps more widely believed. That would be an unfortunate blow for Scottish justice.

Murray intends to appeal the decision to the U.K. Supreme Court in London. I hope that the Supreme Court, in looking at Murray’s appeal, will provide some much-needed clarity about the true meaning and purpose of the “objective test.”

I also hope that the Supreme Court will consider whether the finding of malice made against Murray by the Court in Edinburgh is warranted, and whether the evidence presented to the Court really justifies such a conclusion, which was arrived at without the Court hearing from Murray himself.

Lastly, I hope that the Supreme Court will also look at whether imposing a prison sentence on a man in his sixties of good character with well-known health problems, a family, and two young children, is appropriate in a case such as this. The Supreme Court should look at all these issues, including both at the Court’s verdict and its sentence, its summary of the facts and its analysis of the law.

Even if the Supreme Court were to decide that the verdict was wrong, and that Murray is innocent, I believe it would still be entitled to say that the decision to impose a prison sentence on him was wrong, and would have been wrong even if Murray had been guilty.

It seems that clarification of all of these issues is urgently needed, if balanced reporting of court cases is to be possible, this being a vitally important issue, which goes beyond the serious questions raised about Murray’s treatment in his own case.

Murray appears deserving of the same sort of support that Murray has himself provided to his friend Julian Assange, the imprisoned WikiLeaks publisher.

Alexander Mercouris is a legal analyst, political commentator and editor of The Duran.

The views expressed are solely those of the author and may or may not reflect those of Consortium News.